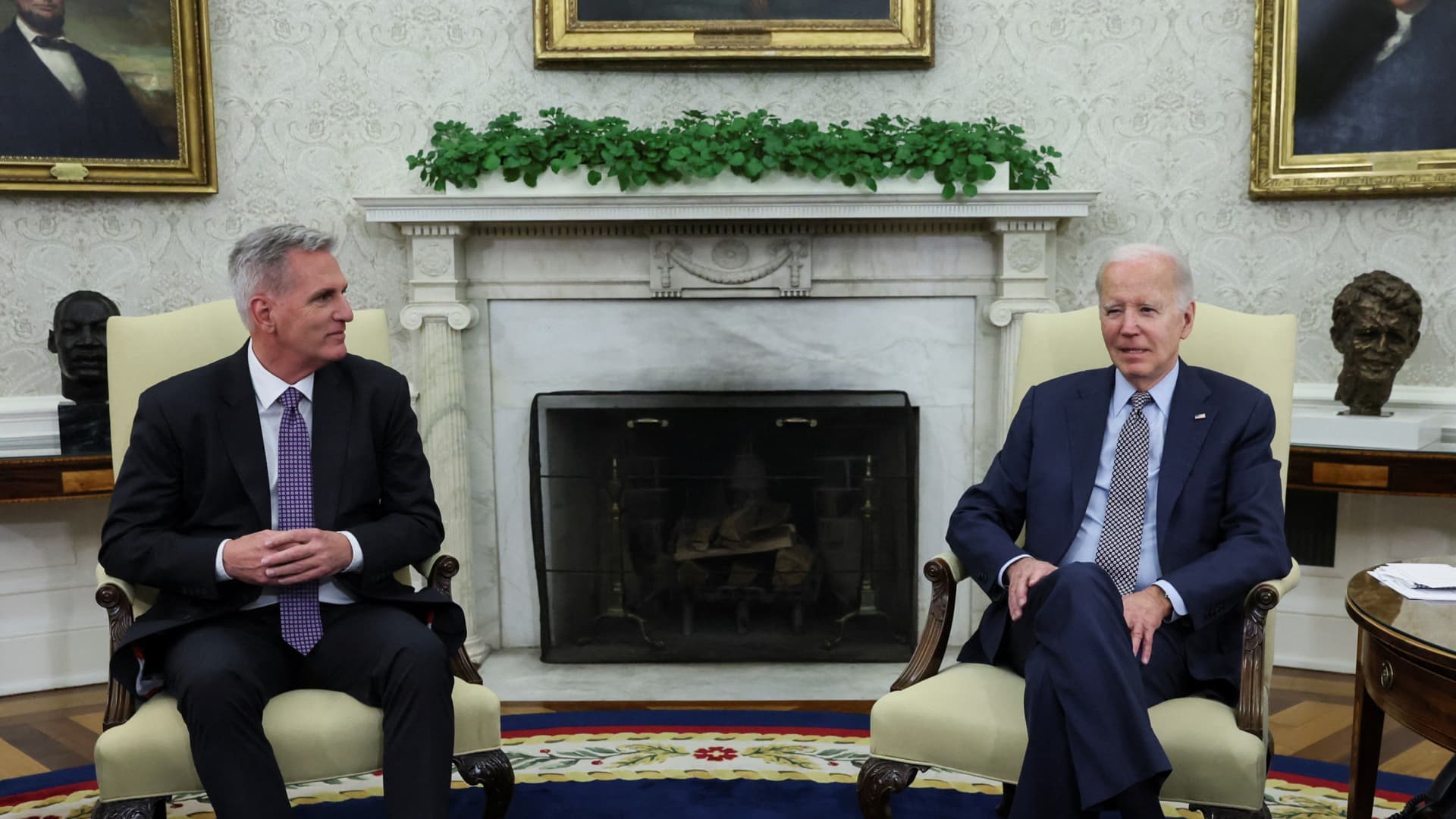

U.S. President Joe Biden hosts debt limit talks with U.S. House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) in the Oval Office at the White House in Washington, U.S., May 22, 2023. REUTERS/Leah Millis

Leah Millis | Reuters

A standoff between the White House and Congressional Republicans over raising the U.S. debt ceiling has pushed the world’s largest economy to the brink of defaulting on its bills.

This is not the first time the formerly procedural mechanism has caused turmoil in Washington. Yet in Denmark — the only other democracy with a similar type of nominal debt ceiling — barely anybody knows it exists.

President Joe Biden and Republican House Speaker Kevin McCarthy held what the latter called a “productive” meeting at the White House on Monday, but a deal remains elusive.

The Republican-led House wants sweeping cuts to federal discretionary spending, new work requirements for welfare recipients and an expansion of mining and fossil fuel production. The White House has so far resisted.

The U.S. will default on its bills for the first time ever, if Democrats and Republicans are unable to break the impasse by June 1. This would likely have serious economic ramifications, including a recession, mass federal job losses and a global stock market collapse.

The debt ceiling has been in effect since 1917 and enables Congress to limit the amount of money the federal government is able to borrow to cover its bills, making up the deficit between what it collects in taxes and spends on government activities already approved by Congress.

It has been lifted 78 times since 1960, last rising by $2.5 trillion in December 2021 to $31.381 trillion.

Once routine, discussions over raising the debt ceiling have increasingly become a platform for political brinkmanship — particularly since 2011, when Republicans also threatened a default if the Obama administration did not grant spending cuts.

The episode prompted S&P Global to issue a first-ever downgrade to the U.S. credit rating, while Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell said at the time that the debt ceiling — and by implication the U.S. economy — was a “hostage worth ransoming.”

The limit was raised unconditionally by the Democratic-led House three times under former Republican President Donald Trump’s administration, but history is now repeating itself.

Separation of church and state

While the U.S. debt ceiling restricts government borrowing to a particular figure, most other economies set debt limits as a percentage of GDP.

For instance, countries that are part of the European Union, under rules set out in the Maastricht Treaty, pledge to keep their public debt below 60% of GDP and to maintain an annual budget deficit of less than 3%.

Denmark is the only other democratic nation in the world with a debt limit set at a fixed nominal figure, yet it never produces the same political and economic turmoil. In fact, it is scarcely even talked about.

This is largely because the Danish debt ceiling was designed to be a synthetic constitutional provision and was set so high that it would never become the “political bargaining chip” it has in the U.S., as government borrowing needs repeatedly run up against it, according to Laura Sunder-Plassmann, associate professor of economics at the University of Copenhagen.

Sunder-Plassmann also explained that Danish politics is less politically polarized than the U.S., with two large and a dozen or more smaller but not insignificant parties represented in parliament.

“While there are definitely arguments to be made for fiscal rules, most advanced countries have opted for non-binding limits on debt to GDP ratios (and deficits) instead of nominal amounts, which while perhaps not perfect at least avoids the kind of debates we now see in the U.S.,” she said via email.

The Danish debt ceiling, or “gældsloft,” was implemented as a constitutional requirement in 1993 after a restructure of the country’s government, and set at 950 billion Danish krone ($137.5 billion). Danish politicians consider it more of a synthetic formality, largely in place to reassure parliament and the public that the government of the day cannot go rogue.

COPENHAGEN, Denmark – Feb. 28, 2023: Members of the Danish Parliament attend a session before a vote at the Folketing. Denmark is the only other country in the world with a debt ceiling comparable to that of the U.S., but it never causes the same political crises that Washington frequently faces.

LISELOTTE SABROE/Ritzau Scanpix/AFP via Getty Images

Denmark has historically retained a strong fiscal position, but suffered a significant deficit in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, prompting the debt ceiling to be increased in 2010 to 2 trillion Danish krone.

This is a hefty limit for a small country of around 6 million people with a national debt of just 323 billion krone at the end of 2022, according to the Danish National Bank.

Denmark is running a budget surplus and has seen its debt fall substantially over the past decade. National debt to GDP declined steadily up until a spike in 2020 caused by the Covid-19 pandemic and fell again to just over 30% of GDP by late 2022.

Jesper Rangvid, professor of finance at the Copenhagen Business School, told CNBC on Tuesday that the Danish system is structured so that political decisions about fiscal policy are confined to the public budget for tax and spending of each year, with the debt ceiling an entirely separate formality.

“It’s simply not discussed in this country because it’s just not an issue, and that is, of course, due to this factor that there has been all of those surpluses for many years on the government budget, and therefore debt has actually been falling for many years,” he explained via telephone from Copenhagen.

“We have the political discussion when we decide on expenditures and taxes and so on, and the debt limit should not be restricting that, which is of course very different to the U.S., where you both have the annual discussions on the budget, on expenditures and incomes, and because you constantly have deficits, then you also have the discussions on the debt limit.”

Rangvid added that, while Danish politicians across the country’s plethora of political parties have a very broad spectrum of views on fiscal policy, the key difference is that the forum for discussing them is confined to the annual budget. Other functions of government therefore cannot be held hostage by the fiscal demands of opposition parties.